Leading lines once again perform an important role in the structure and dynamic of the image below. The convergence of the lines of the floor tiles combined with the centres of the arches and their columns, serve to draw the eyes to the statue in the alcove at the end.

Leading lines once again perform an important role in the structure and dynamic of the image below. The convergence of the lines of the floor tiles combined with the centres of the arches and their columns, serve to draw the eyes to the statue in the alcove at the end.

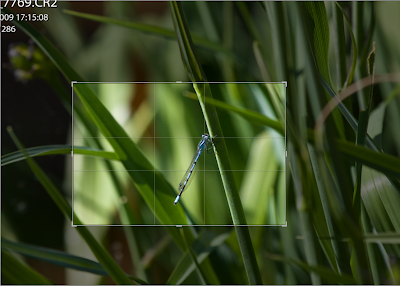

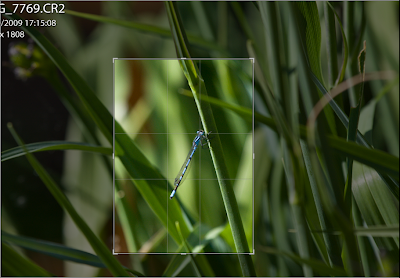

Leading lines are a really powerful tool and they don't have to be straight. The image below isn't a favourite by any stretch of the imagination, however it certainly shows how a curved line formed by the bank of the pool provides a strong leading line.

If you take a look at the post before this one, I've even framed the example image to take advantage of strong leading lines. The more images I look at, the more I realise how much i look for this sort of structure unconciously.

Keep a look out for examples when ever you're taking pictures; pathways, fences, piers, coast lines and many other simple structures can provide great lines that really bring an image to life.